Last week I wrote about my mid-90s work for the litigation focused law firm “Howrey and Simon”. One thing I didn’t mention is how working there was a big kick in the pants to, well, not work there and make free software and then open source a key part of my career.

It was an exciting time in computer science. Linux was maturing and I was downloading SlackWare floppy sets from the internet, or copying them off a CD-ROM1 purchased from Microcenter. Linux was a revelation for me, I loved it and loved learning from it.

Netscape had just gone public and had experienced a huge ‘pop’ in their price that first week of trading. I was riding up the elevator from the under-basement to a higher floor to help an admin with her machine2. As I was going up, a senior ip attorney I’d helped in the past hopped on, pressed the button for his floor and asked me if I had noticed Netscape’s remarkable debut.

I had, and said as much.

He offered (and I’m paraphrasing), “What I don’t get is why the creators of the internet protocol didn’t charge per packet, they’d have made so much money by now and Netscape would have to pay them. It’s really stupid what ‘they’ did.”

I remember mentioning that there *were* protocols that functionally charged for their use in ways the internet protocol and it’s associates had rejected. I remember him snorting dismissively, but maybe that’s time and age changing the actual facts on the ground.

I was trying to imply that without attaching revenue to the protocol’s functioning, it could grow without limits and it would beat out the other WAN/LAN protocols vying for the world’s attention.

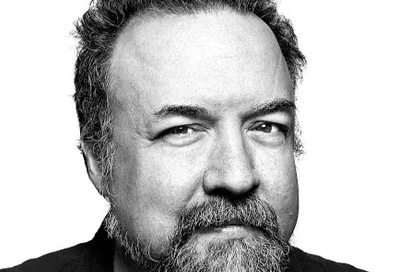

Technically speaking, Vint Cerf , Bob Kahn and the others that came up with the protocols specifically designed them to be more useful the more interconnected they became. While I’m not sure Vint3 expressed it that way to me when we’d end up working together at Google, he’s always been clear that they knew for their offering to grow, they couldn’t yoke it to companies or intellectual property regimes that would specifically work against that growth.

Back to the Lawyer: I remember him saying after I mentioned the other, costly protocols that had been supplanted by the internet protocols that he felt it was a shame ‘they’ didn’t go after the various internet companies and users for royalties, etc. He exited the elevator, or I did, and that was that.

But it stuck with me. As a nerd who was reading all he could about the various protocols that were trying to ‘standardize’ global communications I was firmly for “open” protocols as defined as those that you could adopt without reporting to a central authority or control. At the time, the only real central control point on the internet was DNS and it was run pretty fairly by those early nerds.

Even DNS , you could always point your resolver at another root if you wanted. In those early days the ‘central’ DNS provider (meaning Network Solutions for the NSF) were incentivized to not be so difficult or expensive to work with that you’d use some alt-TLD provider. It wasn’t *likely* but it was technically possible.

It was so possible that in 1997, a commercial company named ‘RealNames’ tried in vain to overlay their own DNS and compete against the ‘real’ DNS in a unsuccessful effort to out-DNS NSI. They were even supported in Microsoft's Internet Explorer for something like five or six minutes.

Now, keep in mind the role of an IP attorney working for Howrey at the time was to exert control over those that might use technology under a patent or other protective ip regime. Litigate, Litigate, Litigate.

This was during a time when my thoughts around the patentability of software, APIs, protocols, hardware, etc. were still germinating. That said, I remember having had a deeply visceral reaction to this lawyer's obvious zeal to control people through technology. I knew he would literally prefer to hold society back until he and his clients had ‘gotten theirs’. Thus, I came to see this elevator ride as the beginning of my path out of the law firm, Washington DC and into the loving arms of free software and open source which would consume the next 30 years of my life.

I think, not sure, we’re talking nearly 30 years ago!

Vint is such a neat fellow. If you have a chance to work with Vint, do it!